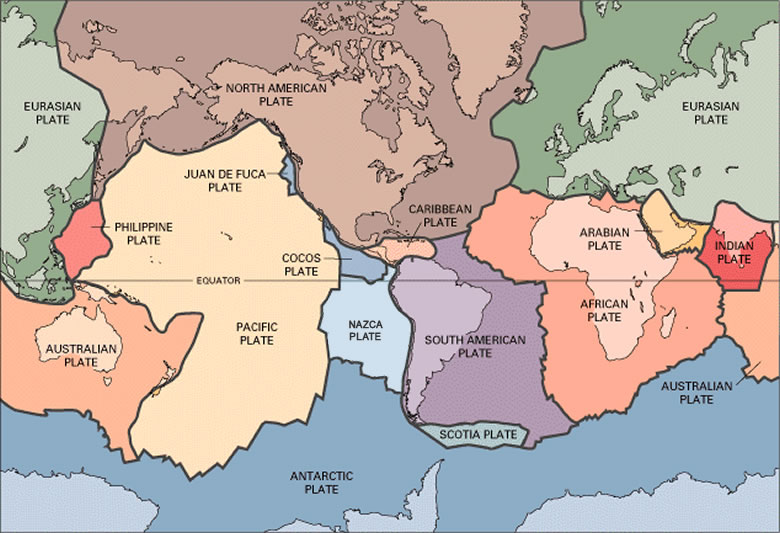

Iceland is on the join of two tectonic plates; it is located right in the centre of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge which spreads apart the continental Eurasian Plate and the North American Plate. The movement that the ridge causes create an opportunity for the magma that resides underneath to rise. This magma upwelling is called the Icelandic Plume. Which means that Iceland is very active with volcanic activity.

- Iceland’s formation is split into three parts: The beginning, during and after the last ice age.

- About a third of the basaltic lava erupted in recorded history have been produced by Icelandic eruptions.

- The oldest rock you can see today in Iceland above sea level is 16 million years old. The older ones have fallen into the sea.

- Five major geothermal power plants exist in Iceland.

- Over 10% of Iceland’s terrain is covered in glaciers. Thereof 8% covered by Vatnajokull Glacier, the largest glacier in Europe.

- From 1963-67 a new island formed right off the South Coast of Iceland. The island which was named Surtsey and remains one of the best researched newly formed islands in the world.

- The English word geyser is taken from the once-powerful Icelandic Geysir, like the famous one seen in the Golden Circle.

Iceland’s positioning means that it’s geology is very lively with a number of active volcanos, numerous hot springs and thermal baths, interesting rock formations and much more.

Eyjafjallajökull has caused most disruption in recent years with the enormous disruptions caused to European air travel in 2010 due to the volcano’s ash cloud.

The most deadly volcanic eruption of Iceland’s history was the so-called Skaftáreldar (fires of Skaftá) in 1783. The eruption was in the crater row Lakagígar (craters of Laki) southwest of Vatnajökull glacier. The craters are a part of a larger volcanic system with the subglacial Grímsvötn as a central volcano. Roughly a quarter of the Icelandic population died because of the eruption. Most died not because of the lava flow or other direct effects of the eruption but from indirect effects, including changes in climate and illnesses in livestock in the following years caused by the ash and poisonous gases from the eruption.

But the Laki eruption had possibly even more widespread effects (even if at the time there were no airlines). In the months after the eruption, a strange haze covered the sky above Europe, making breathing difficult. As the ash and gases from the eruption entered the high layers of the atmosphere, they absorbed moisture and sunlight, changing the climate for years to come.

From 1783 to 1785 accounts from both Japan and America describe terrible droughts, exceptional cold winters, and disastrous floods. In Europe, the exceptionally hot summer of 1783 was followed by long and harsh winters. The resulting crop failures may have triggered one of the most famous insurrections of starving people in history, the French Revolution of 1789-1799.